COSC 4820 Database Systems

Indexes and Introduction to Query Optimization

Ruben Gamboa

Professor

Indexes in SQL

- An index is a data structure that makes it more efficient to retrieve tuples that have a given value

for a given attribute

- For example, an index on the Student ID attribute would make it efficient to find a student with W# "W123456789"

- Or an index on phone number would make it efficient to find a student or students with phone number "307-234-5678"

Indexes in SQL

- In memory, you would solve this problem by using a data structure such as

- a sorted array

- a (binary) search tree

- a hash table

Actually, all of these are used in databases

- A sorted file

- A B-tree with as many children as fit in a disk page

- A hash table, with "buckets" mapping to different disk pages

Note: Sorted files and B-trees can handle comparisons with <, <=, >, >=, and =

But hash tables can only handle equality checks

And (rule of thumb) they are more efficient than the others

Motivation for indexes

- Suppose we need to compute \(S \bowtie S\), where \(S\) is the Students table at UW

- Since \(|S| \approx 14000\), the naive method takes up \(14000^2 =\) 1.96 × 108 steps

- Each step is a disk access, so even if disk I/O is 1ms, that works out to 1.96 × 105 seconds

- Which is 3266.6666667 minutes

- Which is 54.4444444 hours

- Which is 2.2685185 days

- That's a little unfair

Instead of reading each tuple at a time, we can read many tuples at the same time, since they are on the same disk page

Disk I/Os is what matters, so we'll stop worrying about seconds

After all, disks get faster!

Motivation for indexes

- Suppose we need to compute \(S \bowtie S\), where \(S\) is the Students table at UW

- Suppose each disk page can handle 100 students

Since \(|S| \approx 14000\) or 140 pages, the Block Nested Loop join method takes up \(140+140^2 =\) 1.974 × 104 disk I/Os

That's a lot better, but it's still quadratic!

A good index will bring that up to 3.514 × 104 disk I/Os

But it's linear

You'd see an improvement in a larger school

E.g., with 100,000 students, it becomes

- Without an index: \(1000^2 =\) 106 disk I/Os

- With an index: 2.51 × 105 disk I/Os

Motivation for indexes

- The "hard" numbers in the previous slides involve joins

Here's a similar argument with selections

Suppose we need to compute \(\sigma(S)\), where \(S\) is the Students table at UW

Suppose each disk page can handle 100 students

Since \(|S| \approx 14000\) or 140 pages, without an index, we can execute the selection with \(140\) disk I/Os

- A good (and applicable) index will bring that down to 2.5 disk I/Os!

- Actually, it could be a few more, depending on the selectivity of the index (more on this later)

- If we're looking for a single record, then 2.5 disk I/Os is about right

- If we're looking for all students in COSC, it may take \(300\) disk I/Os!

Motivation for indexes

- Indexes can be used to speed up queries that involve selections, e.g.,

SELECT title, year

FROM Movies

WHERE year = 2000

- They can also be used to speed up queries involving joins

SELECT title, year, name

FROM Movies JOIN MovieExecs ON producerC# = cert#

WHERE year = 2000

- And indexes can speed up checking of integrity constraints, e.g., W# must be unique

Declaring Indexes

- Making an index is as easy as calling

CREATE INDEX

CREATE INDEX MovieYearIdx ON Movies(year)

- You would not have to make an index on cert#, because databases automatically create an index on the PRIMARY KEY

Multidimensional Indexes

- You can create an index that spans more than one attribute

CREATE INDEX StudentNameIdx ON Students(first_name, last_name)

- The order of the attributes matters!

- If you know the first_name, but not the last_name, you may still be ab;e to use the index above effectively

- But if you know the last_name and not the first_name, this index is useless

- Note that if the index is a hash index, then knowing one or the other does not help!

- This only helps for indexes that have a sort order, e.g., sorted files or tree indexes

Dropping Indexes

- No surprises here:

DROP INDEX MovieYearIdx

What Indexes to Pick?

What Indexes to Pick?

- The choices you make when picking indexes will likely determine whether the database performance is acceptable or not

- One approach is to create all possible indexes! (Why not?)

- If you have a table with 10 attributes, that's 1023 indexes

- If you have a table with 20 attributes, that's 1.048575 × 106 indexes

- OK, that may be too much

- How about an index on each column?

- 10 attributes means 10 indexes, 20 attributes means 20 indexes

- This is manageable, but consider that each update to the database needs to update each of the indexes!

Basic Tradeoffs

- Indexes may speed up queries with selections and joins

- Indexes may slow down insertions, deletions, and updates

- These are just guidelines!

- An index may slow down a query, e.g, adding an index on "gender" may confuse the optimizer

- An index may speed up an insertion, e.g., by making a constraint check faster

- We'll now discuss some indexes that are usually good ideas

Primary Key Indexes

- It is usually a good idea to have an index on a primary key

- Queries typically join on primary keys, so the index will be used a lot

- The index returns at most one tuple, so at most one page will need to be read

- Suppose we need to compute \(S \bowtie S\), where \(S\) is the Students table at UW

- Suppose each disk page can handle 100 students

- Since \(|S| \approx 14000\) or 140 pages, the Index Nested Loop join method takes up

- \(140\) disk I/Os to read the entire table

- for each tuple, at most one more disk I/O to find the matching tuple

- The grand total is \(140 + 14000 \times 1 =\) 1.414 × 104 disk I/Os

Primary Key Indexes

- Actually, the analysis is slightly wrong

- We counted the disk I/Os to read the tuples, but we never counted the disk I/Os for the index itself

- Rule of thumb: Each lookup on a tree-based index costs 3 disk I/Os (but it would be probably be just 2 on 14,000 rows)

- Rule of thumb: Each lookup on a hash-based index costs 1.5 disk I/Os

- Using these rough estimates, we find

- Using a tree index: \(140 + 14000 \times (1 + 3) =\) 5.614 × 104 disk I/Os

- Using a hash index: \(140 + 14000 \times (1 + 1.5) =\) 3.514 × 104 disk I/Os

Primary Key Indexes

- These indexes are such a good idea that databases routinely build them for us!

- So you should not to build your own primary key indexes, ever

- If you use synthetic keys, then the comparison \(K_1 < K_2\) is probably not meaningful

- I.e., all lookups will be based on equality (\(K1 = \dots\))

- That means you should be using hash indexes on synthetic primary keys

- Hint: The default is usually a tree index

Clustered Indexes

- An index is clustered if all the entries for a given value are on one (or just a very few) pages

- Extreme case: If there's only one matching tuple, then of course it's on only one disk page

- Another case: If the data is sorted on the index attributes, then it's clustered

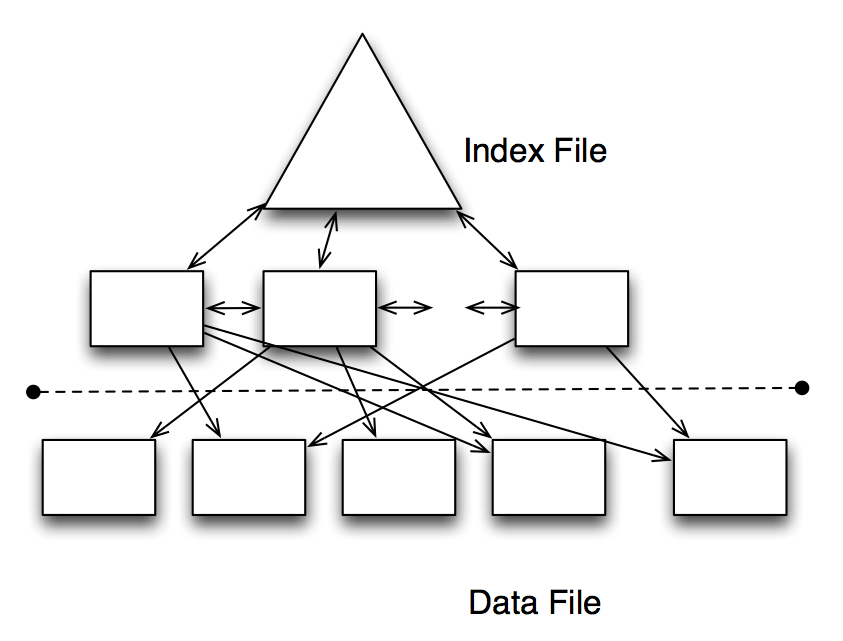

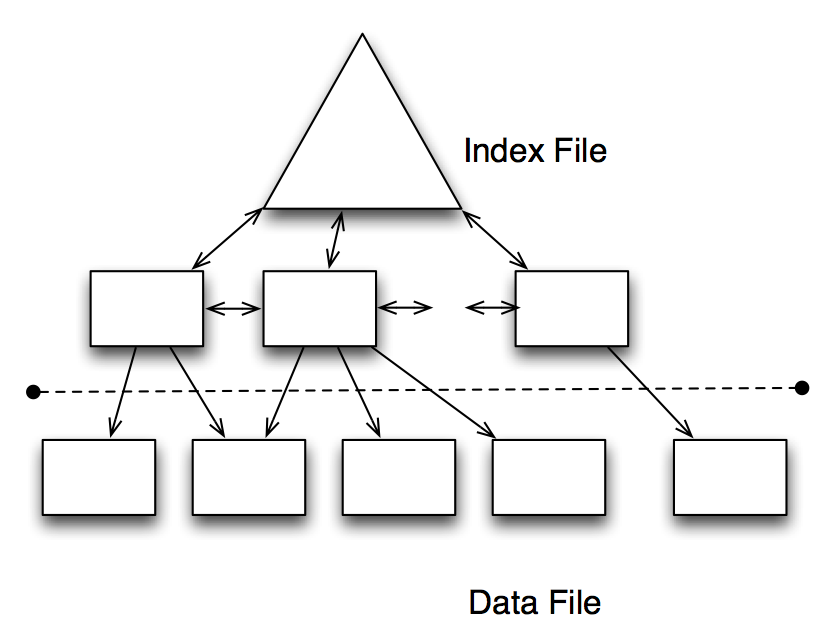

Clustered Indexes

An Unclustered Index

Clustered Indexes

A Clustered Index

Clustered Indexes

SELECT title, year

FROM Movies

WHERE year = 2000

- If the index is clustered, an index on year is very likely to be efficient

- How likely depends on how selective year is in this table

- I.e., if there are only movies from the year 2000, then the index is useless (selectivity 100%)

- But if there are movies from all years from 1980-2010, then the index is good (selectivity \(\approx\) 3%)

Clustered Indexes

SELECT title, year

FROM Movies

WHERE year = 2000

- If the index is unclustered, an index on year may be worse than useless

- Even if there is data from 1980-2010, we still have to read each tuple separately

- That means we need \(0.03 \times N\) disk I/Os

- If a block holds more than 33 records, we would be better off ignoring the index!

Picking Indexes

- It's hard to pick indexes in a vacuum

- What you really need is a list of queries that are important to your application(s)

- Also, these queries should be weighted, since some queries may be more important or frequent than others

- With this information, you can compare the cost of implementing different indexes

Example

- Q1, with probability \(.6\)

SELECT movieTitle, movieYear

FROM StarsIn

WHERE starName = ?

- Q2, with probability \(.3\)

SELECT starName

FROM StarsIn

WHERE movieTitle = ? AND movieYear = ?

- Q3, with probability \(.1\)

INSERT INTO StarsIn VALUES(?,?,?)

Example (Assumptions)

- StarsIn takes up 10 pages

- Typically, a star appears in 3 movies and each movie has 3 stars

- The 3 movies a star is in will be in different pages of StarsIn, so it will take 3 disk I/Os to fetch these 3 movies, even with an index

- 1.5 disk accesses are required to read the index for an equality lookup

- For inserts, we need 1 disk I/O to read the original page, 1 disk I/O to write the modified page, and 2.5 disk I/Os to update the index (1.5 read, 1 write) -- for a total of 4.5 disk I/Os

Example

| Query | No Index | starName Index | movieTitle Index | Both Indexes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 10 | 4.5 | 10 | 4.5 |

| Q2 | 10 | 10 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| Q3 | 2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 7 |

| Total | 9.2 | 6.15 | 7.8 | 4.75 |

- Q1, with probability \(.6\)

SELECT movieTitle, movieYear

FROM StarsIn

WHERE starName = ?

- Q2, with probability \(.3\)

SELECT starName

FROM StarsIn

WHERE movieTitle = ? AND movieYear = ?

- Q3, with probability \(.1\)

INSERT INTO StarsIn VALUES(?,?,?)

Example

| Query | No Index | starName Index | movieTitle Index | Both Indexes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 10 | 4.5 | 10 | 4.5 |

| Q2 | 10 | 10 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| Q3 | 2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 7 |

| Total | 6 | 5.6 | 6.15 | 5.75 |

- Q1, with probability \(.3\)

SELECT movieTitle, movieYear

FROM StarsIn

WHERE starName = ?

- Q2, with probability \(.2\)

SELECT starName

FROM StarsIn

WHERE movieTitle = ? AND movieYear = ?

- Q3, with probability \(.5\)

INSERT INTO StarsIn VALUES(?,?,?)

Picking Indexes Globally

- We only considered two indexes

- But what if we had dozens of tables with dozens of attributes?

- This is where automated tools come in

- A typical approach is to choose indexes greedily

- First, fix a workload of queries

- Consider the cost of executing these queries with no index

- Now consider the cost of executing these queries with one (out of many possible) indexes

- Pick the index that works best

- Keep adding one index at a time, until it stops helping

The Query Optimizer: Cost Estimation

Approach to Selections

- Find the most selective access path

- Selective: retrieve fewest number of tuples up front (using an index)

- Apply any remaining conditions to the tuples returned

- In other words, pick most selective index, and filter remaining tuples

- Yeah, that's the big reveal

- Now, onto the details

Approach to Selections

- What is the most selective access path?

- Answer: An index or file scan that (we estimate) will require the fewest page I/O operations

- The remaining terms on the condition are applied to the tuples read with the most selective access path

- But the remaining terms do not affect the #tuples or #pages fetched

- So the cost of the other terms is zero (since we only count I/O)

Example

- Consider this condition:

date < 5/1/19 AND voter_id=5 AND precinct_id=3 Here are two different query plans:

- Use a B+ tree on the date field, then filter the remaining tuples using the condition voter_id=5 AND precinct_id=3

- Use a hash index on voter_id and precint_id and then check each tuple to see if it matches day<5/1/19

- Main Question: Which is better? How do we even think about answering this question?

Implementing Selections

- Cost of using an index for selection depends on

- #matching tuples

- clustering

- Cost of finding matching tuples is usually small

- Cost of retrieving matching tuples is

- small for clustered index

- large for unclustered index (linear in #matches)

- totally impractical for unclustered index when many tuples match

Cost Example

SELECT *

FROM MovieStars

WHERE name < 'C'

- "Benign" assumptions:

- Uniform distribution of names

- I.e., about 10% (2/26) of tuples qualify

- 40,000 tuples in 500 pages (80 per page)

- Note: Catalog knows min and max of names, so it can compute the percentage using the uniformity assumption

- Note: But if uniformity assumption isn't realistic, keep histograms instead!

Cost Example

SELECT *

FROM MovieStars

WHERE name < 'C'

- I.e., about 10% (2/26) of tuples qualify

- 40,000 tuples in 500 pages (80 per page)

- Cost estimates:

- Clustered index: a little more than 50 I/Os (e.g., 3+50)

- Unclustered index: a little more than 4,000 I/Os (e.g., 3+4,000)

Implementing Joins: Nested Loop Joins

\[R(x,y) \bowtie S(y,z)\]

foreach tuple r in R do:

foreach tuple s in S where r.y=s.y do:

add <r,s> to result

- If there is an index on the join column of one relation (i.e., on column y of relation S), make it the inner relation to exploit the index:

- Cost: #Pages(R) + #Tuples(R)*(IndexLookup(S)+Lookup(S))

- Cost assumptions:

- R: 100,000 tuples in 100 pages (1,000 per page)

- S: 40,000 tuples in 500 pages (80 per page)

- index cost is 1.2 (hash) or 2-3 (tree)

- read matching tuple of S is 1

Implementing Joins: Nested Loop Joins

\[R(x,y) \bowtie S(y,z)\]

foreach tuple r in R do:

foreach tuple s in S where r.y=s.y do:

add <r,s> to result

- Hash index, column y of table S

- Scan R: 1,000 pages

- For each (100,000) R tuple:

- 1.2 to read from the hash index on S.y (on average)

- 1 to get corresponding tuple from S

- Total cost: 221,000

Implementing Joins: Nested Loop Joins

\[R(x,y) \bowtie S(y,z)\]

foreach tuple s in S do:

foreach tuple r in R where r.y=s.y do:

add <r,s> to result

- Hash index, column y of table R

- Scan S: 500 pages

- For each (40,000) S tuple:

- 1.2 to read from the hash index (on average)

- 2.5 movies per star on average (100,000/40,000)

- Cost to fetch movies is 1 (for clustered) or 2.5 (unclustered)

- Total cost: 88,500 (clustered) or 148,500 (unclustered)

Implementing Joins: Sort-Merge Joins

\[R(x,y) \bowtie S(y,z)\]

- Basic Idea: Sort both \(R(x,y)\) and \(S(y,z)\) on \(y\)

- Note: It's possible that \(R\) or \(S\) is already sorted on \(y\)

- Then read the sorted versions of \(R\) and \(S\) as in merge sort

- The merge implements the join

- Some \(y\) values will be in both \(R\) and \(S\), e.g., \(y_1\), \(y_2\), ..., \(y_n\)

- For each \(y_i\), let \(X_i\equiv\{x \mid \langle x, y_i \rangle \in R\}\) and \(Z_i\equiv\{z \mid \langle y_i,z \rangle \in S\}\)

- The answer is the cross product \(X_i \times \{y_i\} \times Z_i\)

- We can implement that cross product by scanning \(R\) only once, but possibly scanning each \(Z_i\) once per tuple in \(X_i\)

- Hopefully,all or most of the pages of \(Z_i\) remain in memory, so we can do a single scan of \(S\) as well

Cost of Sort-Merge Joins

Cost: Sort(R) + Sort(S) + #Pages(R) + #Pages(S)

- #Pages(R) + #Pages(S) is the likely (and best possible) cost of the merge operation

- But the merge could cost as high as #Pages(R) * #Pages(S)

- This depends entirely on the characteristics of the data

- Worst case: There is only one distinct \(y\), so \(R \bowtie S \approx R \times S\)

Cost of sorting depends on how much data we can load into memory

External sorts require a number of passes

For these tables, 2 passes should be enough

Each pass reads and writes data, so the total cost is

Cost: \(2\cdot2\cdot1,000 + 2\cdot2\cdot500 + 1,000 + 500 = 7,500\) I/O operations

Index Join or Sort-Merge Join?

| Join Type | Cost |

|---|---|

| Index Join | 221,000 I/O ops |

| Sort-Merge Join | 7,500 I/O ops |

- Easy call, right?

- Not so fast!

- Suppose the join appears in the query \(\sigma(R \bowtie S)\)

- And suppose the selection filters the movies for a specific movie star or even a few stars

- Index join could be orders of magnitude faster than sort-merge join!

- Sort-merge still has to scan all records, while index join may fetch only the necessary records

- Moral of the story: Optimization must be global

System R Optimizer

System R Optimizer

- System R project developed the first query optimizer

- It is still the most widely used approach today

- Works really well for queries with at most 10 joins

- Cost estimations:

- Statistics (in system catalog) used to estimate cost of operations and result sizes

- Cost considers a combination of CPU and I/O costs

System R Optimizer: Query Plans

Query plan space:

- It's too big

- I.e., there are too many (exponential) possible query plans, so there is not enough time to consider them all

- Solution: consider only left-deep plans

- The tree looks more like a linked list!

- This allows output of each operator to be pipelined into the next operator without storing results in temporary tables

- This depends on the cursor interface

System R Optimizer: Cost Estimator

- Optimizer must estimate cost of each plan considered

Estimate cost of each operation in query plan

- We've already discussed how to estimate the cost of operations (sequential scan, index scan, joins, etc.)

- This depends on the size of the inputs

Must also estimate size of result for each operation in tree!

- Use information about the input relations

- Make "reasonable" assumptions

- Assumption: uniformity of data

- Assumption: independence of conditions in selections and joins

Quality of optimizer is empirical: Does it find good query plans for typical queries?

Size Estimator

SELECT attributes

FROM relations

WHERE cond1 AND cond2 AND ... AND condk

- Maximum #tuples in result is the cardinality of the cross product of relations in the FROM clause

- I.e., worst case is always the cross product

- Reduction factor (RF) associated with each condition reflects the impact of the condition in reducing the result size

Cardinality of result = Max #tuples * RF1 * RF2 * ... * RFk

Assumes conditions are independent

Reduction Factors

- The secret to having good size estimators is to know the reduction factors of different types of conditions

| Condition | Reduction Factor |

|---|---|

| col = value | \(1 / NKeys(I)\), for some index \(I\) on col |

| col1 = col2 | \(1 / \max(NKeys(I_1),NKeys(I_2))\), for indexes \(I_1\) and \(I_2\) on col1 and col2 |

| col1 > value | \(\frac{High(I)-value}{High(I)-Low(I)}\), for some index \(I\) on col |

Examples: Sample Schema

StarsIn (name, title, year)

MovieStar (name, address, genre, birthdate, rating)

Similar to old schema, but with rating added to MovieStar

StarsIn

- Each tuple is 40 bytes long, 1,000 tuples per page, 1,000 pages

MovieStar

- Each tuple is 500 bytes long, 80 tuples per page, 500 pages

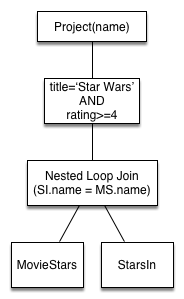

Motivating Example

SELECT MS.name

FROM StarsIn AS SI, MovieStars AS MS

WHERE SI.name = MS.name AND SI.title='Star Wars' AND MS.rating>=4

- Cost: 500 + 500*1,000 I/Os

- Scan MovieStars, then Scan StarsIn for each MovieStar block

- Actually not the worst plan!

- Can be improved considerably, e.g., by using indexes

- Goal is to find more efficient plan that computes the same answer

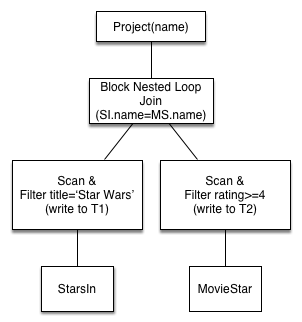

Alternative Plan #1

SELECT MS.name

FROM StarsIn AS SI, MovieStars AS MS

WHERE SI.name = MS.name AND SI.title='Star Wars' AND MS.rating>=4

- Main difference: push selects

- With 5 buffers, cost of plan:

- Scan StarsIn (1,000) + write T1 (1 page, assuming < 1,000 matches)

- Scan MovieStars (500) + write T2 (200 pages, if ratings are 1-5)

- Sort T1 (2), sort T2(2*3*200), merge (1+200)

- Total: 1,701 (selections) + 1,403 (join) = 3,104 page I/Os

Alternative Plan #1

SELECT MS.name

FROM StarsIn AS SI, MovieStars AS MS

WHERE SI.name = MS.name AND SI.title='Star Wars' AND MS.rating>=4

- Using BNL join, join cost = 1+1*200

- Total: 1,701 (selections) + 201 (join) = 1,902 page I/Os

- If we push projections, T2 has only name and title

- That lowers the #pages requires (albeit slightly)

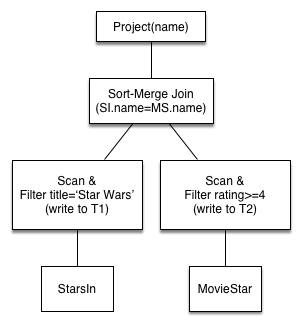

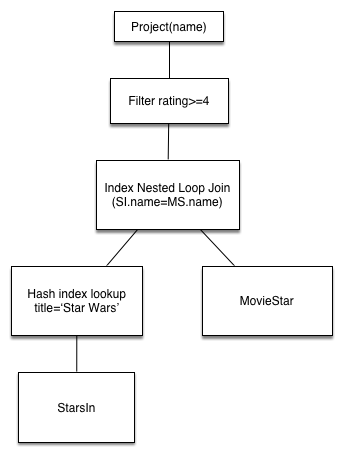

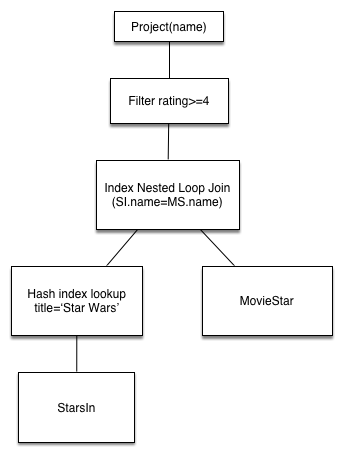

Alternative Plan #2

SELECT MS.name

FROM StarsIn AS SI, MovieStars AS MS

WHERE SI.name = MS.name AND SI.title='Star Wars' AND MS.rating>=4

- Suppose we have a clustered index on title of StarsIn

- We get 1,000,000/40,000 = 25 StarsIn tuples for each MovieStar tuple

- INL join, Filter, and Project are all pipelined, so there's no benefit to pushing the projection in

- Pushing the selection rating >= 4 into the join would make it worse, because we can't use index on MovieStars

Alternative Plan #2

SELECT MS.name

FROM StarsIn AS SI, MovieStars AS MS

WHERE SI.name = MS.name AND SI.title='Star Wars' AND MS.rating>=4

- Cost:

- Selection of StarsIn: 2.2 I/O ops

- For each movie, must get matching MovieStar tuple (10*1.2)

- Question: How many different movies in StarsIn, and how does that translate to MovieStar?

- Total cost: 15 I/O operations

Summary

SELECT MS.name

FROM StarsIn AS SI, MovieStars AS MS

WHERE SI.name = MS.name AND SI.title='Star Wars' AND MS.rating>=4

| Method | Cost |

|---|---|

| Nested loop | 500,500 |

| Push selections | 3,104 |

| Push selections, BNL join | 1,902 |

| Push selections & projections, BNL join | ~1,700 |

| Clustered index on StarsIn | 15 |

Extended Example

- Consider this query (inspired by a previous course project):

SELECT count(distinct courses.crn), sum(courses.credits)

FROM enrolled, students, courses

WHERE enrolled.wnumber = students.wnumber

AND enrolled.crn = courses.crn

AND courses.subject = 'COSC'

- What is the best way to execute it?

Extended Example

SELECT count(distinct courses.crn), sum(courses.credits)

FROM enrolled, students, courses

WHERE enrolled.wnumber = students.wnumber

AND enrolled.crn = courses.crn

AND courses.subject = 'COSC'

- First, find all courses with subject=COSC

- Then, use that to find all the enrolled records for COSC courses

- Finally, look up the students enrolled in those courses

- That's my buest guess, but let's ask the database to EXPLAIN its plan

Extended Example

EXPLAIN

SELECT count(distinct courses.crn), sum(courses.credits)

FROM enrolled, students, courses

WHERE enrolled.wnumber = students.wnumber

AND enrolled.crn = courses.crn

AND courses.subject = 'COSC'

| id | select_type | table | type | possible_keys | key | key_len | ref | rows | Extra |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SIMPLE | students | index | PRIMARY | PRIMARY | 12 | 10473 | Using index | |

| 1 | SIMPLE | enrolled | ref | PRIMARY,wnumber | wnumber | 12 | students.wnumber | 2 | Using index |

| 1 | SIMPLE | courses | eq_ref | PRIMARY | PRIMARY | 7 | enrolled.crn | 1 | Using where |

- Note that the only tables we actually read is courses and enrolled

- We only read the index for students

Extended Example

EXPLAIN

SELECT count(distinct courses.crn), sum(courses.credits)

FROM enrolled, students, courses

WHERE enrolled.wnumber = students.wnumber

AND enrolled.crn = courses.crn

AND courses.subject = 'COSC'

- Why aren't we following the "obvious" efficient plan?

- Problem: possible_keys for courses does not include subject

- So our imagined "optimal" query plan is no good

Extended Example

EXPLAIN

SELECT count(distinct courses.crn), sum(courses.credits)

FROM enrolled, students, courses

WHERE enrolled.wnumber = students.wnumber

AND enrolled.crn = courses.crn

AND courses.subject = 'COSC'

CREATE INDEX courses_subject_idx

USING HASH

ON courses (subject)

Extended Example

EXPLAIN

SELECT count(distinct courses.crn), sum(courses.credits)

FROM enrolled, students, courses

WHERE enrolled.wnumber = students.wnumber

AND enrolled.crn = courses.crn

AND courses.subject = 'COSC'

| id | select_type | table | type | possible_keys | key | key_len | ref | rows | Extra |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SIMPLE | courses | ref | PRIMARY, courses_subject_idx |

courses_subject_idx | 7 | const | 58 | Using where |

| 1 | SIMPLE | enrolled | ref | PRIMARY,wnumber | PRIMARY | 7 | courses.crn | 9 | Using index |

| 1 | SIMPLE | students | eq_ref | PRIMARY | PRIMARY | 12 | enrolled.wnumber | 1 | Using index |

Extended Example

EXPLAIN

SELECT count(distinct courses.crn), sum(courses.credits)

FROM enrolled, students, courses

WHERE enrolled.wnumber = students.wnumber

AND enrolled.crn = courses.crn

AND courses.subject = 'COSC'

- Enrolled has a PRIMARY index (on crn & wnumber), and a SECONDARY index on wnumber

- But no indexes on crn

- Would that help?

CREATE INDEX enrolled_crn_idx

USING HASH

ON enrolled (crn)

Extended Example

EXPLAIN

SELECT count(distinct courses.crn), sum(courses.credits)

FROM enrolled, students, courses

WHERE enrolled.wnumber = students.wnumber

AND enrolled.crn = courses.crn

AND courses.subject = 'COSC'

| id | select_type | table | type | possible_keys | key | key_len | ref | rows | Extra |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SIMPLE | courses | ref | PRIMARY, courses_subject_idx |

courses_subject_idx | 7 | const | 58 | Using where |

| 1 | SIMPLE | enrolled | ref | PRIMARY,wnumber, enrolled_crn_idx |

enrolled_crn_idx | 7 | courses.crn | 6 | Using index |

| 1 | SIMPLE | students | eq_ref | PRIMARY | PRIMARY | 12 | enrolled.wnumber | 1 | Using index |

- BTW, the only table actually read is courses

Extended Example

SELECT count(distinct courses.crn), sum(courses.credits)

FROM enrolled, students, courses

WHERE enrolled.wnumber = students.wnumber

AND enrolled.crn = courses.crn

AND courses.subject = 'COSC'

| Index | Cost |

|---|---|

| S(w#), E(crn,wnumber) | 20,946 |

| C(subj), E(crn,wnumber), S(w#) | 522 |

| C(subj), E(crn), S(w#) | 348 |

Summary

- The are several alternative evaluation algorithms for each relational operator

- A query is evaluated by converting to a tree of operators and evaluating the operators in the tree

- You must understand query optimization in order to fully understand the performance impact of a given database design (relations, indexes) on a workload (set of queries)

Summary

- To optimize a query:

- Consider a set of alternative plans

- Must prune search space

- Typically: only consider left-deep plans

- Estimate cost of each considered plan

- Must estimate size of result and cost for each plan node

- Key issues: Statistics, indexes, operator implementations